This year, extreme rainfall has devastated communities from California to the Southeast. In the Midwest, flooding has caused billions of dollars in damage. While ice jams and levee failures have contributed to the flooding, heavy downpours haven’t helped.

Downpours like these are strengthened by human-caused climate change. More than 70 percent of the planet’s surface is water, and as the world warms, more water evaporates into the atmosphere. That additional moisture makes heavy rain heavier, increasing the risk of flooding.

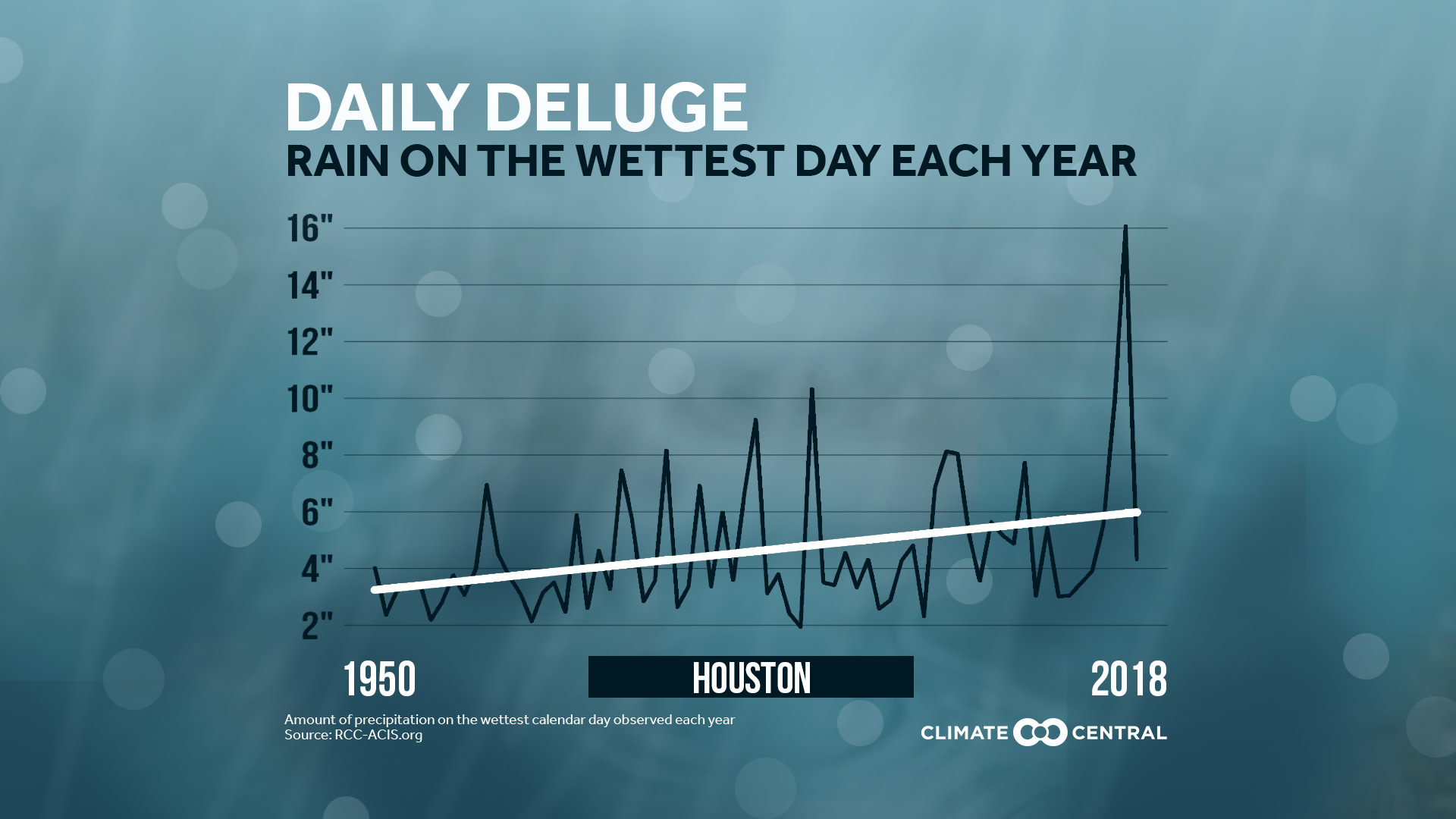

Floods are especially common on the rainiest day of the year — the single calendar day with the most precipitation. So Climate Central tracked how those wet days have changed over time in 244 U.S. cities.

79 percent have seen their rainiest days get even wetter since 1950. Houston, Texas tops the list with an increase of 2.78 inches — even without the recent flash flooding. In 32 cities, the average precipitation on the year’s wettest day has increased by an inch or more. Though an extra inch of rain may not sound like much, consider that most rainy days fail to deliver an inch of precipitation in the first place.

In addition to getting wetter, extreme downpours are happening more frequently. The national frequency of 1”, 2”, and 3” storms has markedly increased since 1950, and as most cities observe similar trends, threats of flooding are spiking upward.

1"

TITLE: JPG • PNG

NO TITLE: JPG • PNG

2"

TITLE: JPG • PNG

NO TITLE: JPG • PNG

3"

TITLE: JPG • PNG

NO TITLE: JPG • PNG

This spring’s floods have damaged thousands of homes and state highway miles, while causing nearly $1 billion in farming losses. Only 8% of monitored levees in the U.S. are rated in “acceptable” condition, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Other floods have endangered public health, washing sewage into waterways and creating habitats for disease-carrying insects. Cities can minimize impacts by developing hazard mitigation plans and managing stormwater with permeable surfaces, but the nation has a long way to go.

Curbing our climate-warming emissions would help. If greenhouse emissions continue unchecked, the type of intense rainstorm that statistically happens only once every five years could happen two or three times as often by late-century. But if the world makes significant emissions cuts — roughly in line with the Paris Agreement pledges — the increase in frequency could be cut in half. In a waterlogged world, that difference would be critical.

Methodology: Using data from the Applied Climate Information System, Climate Central identified the calendar day each year with the highest precipitation for each station. Trendlines are based on a mathematical linear regression. Trends in one-, two-, and three-inch rainfall analyses are based on a methodology from Brian Brettschneider, a climate researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.