KEY CONCEPTS

Heat is the top weather killer, surpassing hurricanes and tornadoes.

An estimated 12,000 Americans die of heat-related causes annually, according to research by scientists at Duke University. That’s roughly on par with annual deaths from gun homicides.

More than 80 percent of heat’s victims are over 60, researchers have found. The baby boomer generation (born between 1946-1964) will be among those immediately hardest hit by climate change, as their increasing vulnerability to extreme heat coincides with rising temperatures.

Physicians and emergency planners say seniors’ best defense against heat is social connection, with family and neighbors checking on elders who are alone in sweltering weather. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic impedes those in-person connections, while restricting capacity in traditional cooling centers and public areas.

Climate Central released a research brief today, Seniors at Risk: Heat and Climate Change, to provide more background on this issue: Read the full research brief

Heat is the top killer among all types of weather hazards, including hurricanes and tornadoes. But hospitals and health care providers do not always report heat-related illnesses or heat as an underlying cause of a death, making it hard to measure the actual impact of extreme heat on health.

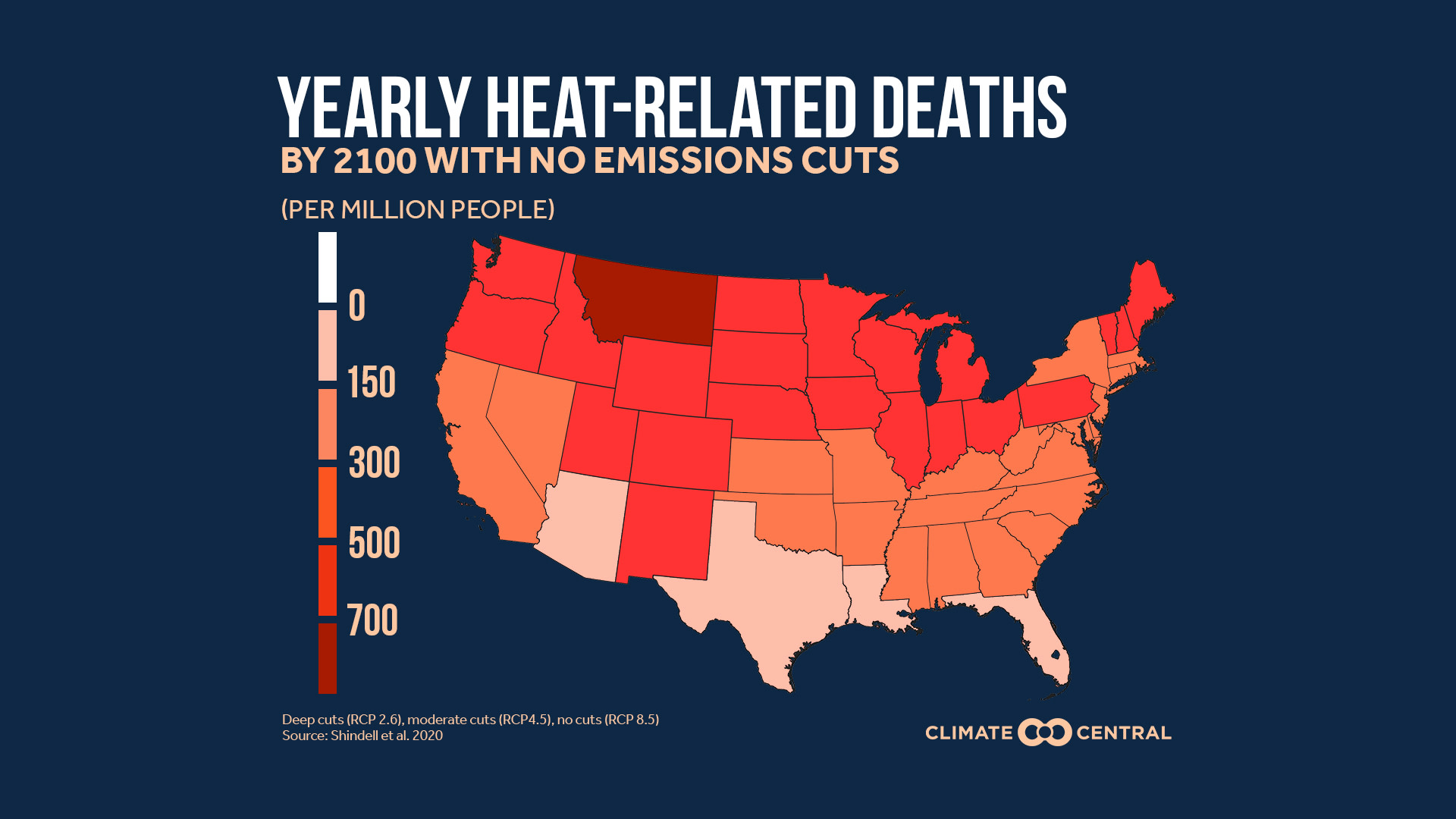

An estimated 12,000 Americans die of heat-related causes annually, according to research by scientists at Duke University, a number roughly comparable to annual deaths from gun homicides. The April 2020 study dramatically increased the estimates of current deaths and future deaths, surpassing the 2018 National Climate Assesment’s 2100 projection by a factor of 10.

More than 80 percent of those dying from heat-related illnesses are over 60, researchers have found. The baby boomer generation (born between 1946-1964) will be among those immediately hardest hit by climate change, as their vulnerability to extreme heat coincides with rising temperatures.

Heat and dehydration stress older people, notably those with chronic medical conditions. Moreover, certain medications can make peoples' bodies more vulnerable to extreme heat and dehydration. Physiological studies show that whether or not they face health issues, seniors are less able to sense heat or to sweat, and are less apt to feel thirst and seek fluids when dehydrated, compared to younger adults. As our bodies age, we don’t regulate internal heat as well. Poor physical fitness or being overweight makes these problems worse.

Planning for excessive heat varies across the U.S., reflecting climate and community differences. Heat events can be deadliest in cities with lower average temperatures, where residents are less adapted to heat. Conditions can be especially bad in low-income areas where seniors are less able to afford air conditioning, the housing is of lower quality (absorbing and retaining more heat), and communities of color make up a disproportionate fraction of the population.

Physicians and emergency planners say seniors’ best defense against heat is social connection, with family and neighbors checking on elders who are alone in sweltering weather. Experts have found common strategies that all communities can use to avert senior heat deaths. With the additional threat of COVID-19, cities are also looking at funding for air conditioners and utility bills, closing streets to allow more outdoor space, parking air-conditioned buses as dispersed cooling centers, and even renting hotel rooms for vulnerable homeless people.

POTENTIAL LOCAL STORY ANGLES

Is your community prepared for heat events during the COVID-19 pandemic?

The Global Heat Health Information Network has issued a peer-reviewed technical brief to help communities and health systems prepare for hot weather events during the coronavirus pandemic. The EPA’s Excessive Heat Events Guidebook highlights best practices that have been employed to save lives during excessive heat events in different urban areas. The National Integrated Heat Health Information System provides climate and health outlooks, as well as strategies that communities and individuals are taking to mitigate future heat.

How is heat affecting the public health of seniors and vulnerable populations near you?

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) tracks health and heat data through its public health tracking network for 25 states and New York City. Summer heat and sun can also cause air stagnation and accumulation of ground-level ozone. Find out more about climate change and air quality from the American Lung Association, and check out their rankings of cleanest cities.

EXPERTS TO INTERVIEW

Drew Shindell, Nicholas Distinguished Professor of Earth Science, Duke University Research interests include: climate change, air quality, and links between science and policy. drew.shindell@duke.edu

Dr. Jay Lemery, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine Research interests include: effects of climate change on human health, remote medical care. john.lemery@ucdenver.edu

Kristie Ebi, Professor, Environmental and Occupational Health, Global Health, University of Washington Research interests include: impacts of and adaptation to climate variability and change, including extreme events, thermal stress, vector-borne diseases, foodborne safety and security. krisebi@uw.edu

METHODOLOGY

National and state-level heat-related mortality data was obtained by Shindell et al. 2020.