KEY POINTS

October is “king tide” season, bringing the highest high tides of the year for much of the U.S. coastline

As sea levels rise, tidal flooding is increasing across the country

Inland flooding is also on the rise in every region of the contiguous U.S.

Communities across the United States are trying to build resilience to flooding

U.S. coastal communities recovering from the flooding generated by Hurricane Florence may need to brace themselves for another source of inundation this month.

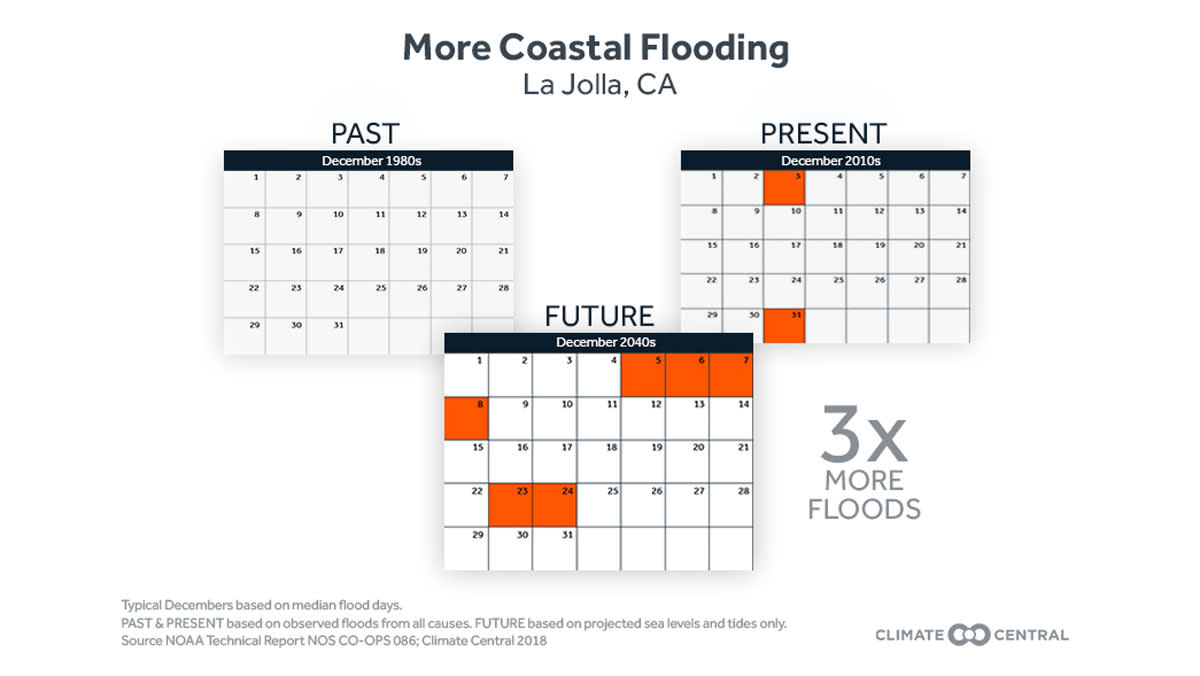

October is the peak of “king tide” season on the East and Gulf Coasts; on the West Coast, the peak comes in December. High tides will be higher in the coming weeks than during most other times of the year, thanks to a mix of ocean currents, water temperatures, and solar and lunar gravity. The tidal flooding that sometimes results can damage property, degrade infrastructure, and require expensive cleanup.

“In many places, it only takes a little standing water to impede municipal services and bring transportation to a standstill, disrupting daily life in a community,” said Dr. Maya Buchanan, Climate Central’s sea-level rise scientist.

As sea levels rise due to a warming planet, tidal flooding will become much more frequent. In an average year this decade, 30 sites selected by Climate Central on the East, Gulf, and West Coasts saw a total of 153 days of floods, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In an average year in the 2040s, those 30 locations would see around 2,850 floods. (While flood count projections for future decades include only the effects of sea-level rise and high tides, flood counts for past and present decades are also shaped by storm surges and other temporary factors.) These projections assume that global mean sea level will rise this century by around 3 feet (a little more than the height of a kitchen countertop), which climate scientists believe is a relatively conservative estimate. Under the same scenario, most coastal regions in the contiguous United States could see tidal flooding every day of the year by 2100, according to an analysis by NOAA.

Inland flooding is also projected to worsen in the years ahead. Every region of the contiguous United States has seen increases in the most extreme precipitation eventssince the 1950s. And by 2050, 42 of the lower 48 U.S. will likely face increased heavy runoff from rainfall — one of the key ingredients in producing inland floods. Florida and California are particularly vulnerable to inland flooding, with more than one million people living in FEMA’s 100-year floodplain in each state. In Tennessee and Arkansas, more than 200,000 people live in such areas.

Inland flooding, or flooding of rivers and streams, is related to water runoff and depends on many factors in addition to rainfall amounts. See full multimedia package on inland flooding here.

“The frequency and magnitude of extreme precipitation events has been increasing over the past two to three decades, particularly in the eastern U.S.,” said Dr. Kenneth Kunkel, a research professor at North Carolina State University. “Future increases in atmospheric water vapor, a certain outcome of additional global warming, will favor a continuation of the upward trends in extreme precipitation. It would be prudent to protect society from this likely eventuality by increasing resilience to flooding."

Communities and governments are taking a number of steps to deal with the challenge of flooding. Fort Collins, Colorado, invested in improving its flood-warning system, built holding ponds to slow flash-flooding, and introduced new building standards in the years after a devastating 1997 flood. On the coast, cities have built networks of pumping stations, raised roadways and other essential infrastructure, and installed devices that prevent tidal waters from backing up through urban storm drains. In northwestern Florida, an increasing number of communities have developed “living shorelines,” which use natural features such as oyster shells and marsh grasses to slow coastal erosion. Some cities, such as Boston, have ruled that certain construction projects must incorporate the potential effects of climate-change impacts into their design.

“Boston is taking climate adaptation seriously,” said Mia Mansfield, the program manager of Climate Ready Boston. “We are implementing our 'Climate Ready Boston' strategy through neighborhood coastal resilience plans, new zoning and infrastructure standards in the future floodplain, and a citywide community climate leadership program.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

SciLine: A local science-expert resource for journalists

Surging Seas Risk Finder: A guide to sea-level and coastal flood risks, by location

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit: Case studies on flooding and community resilience