KEY CONCEPTS

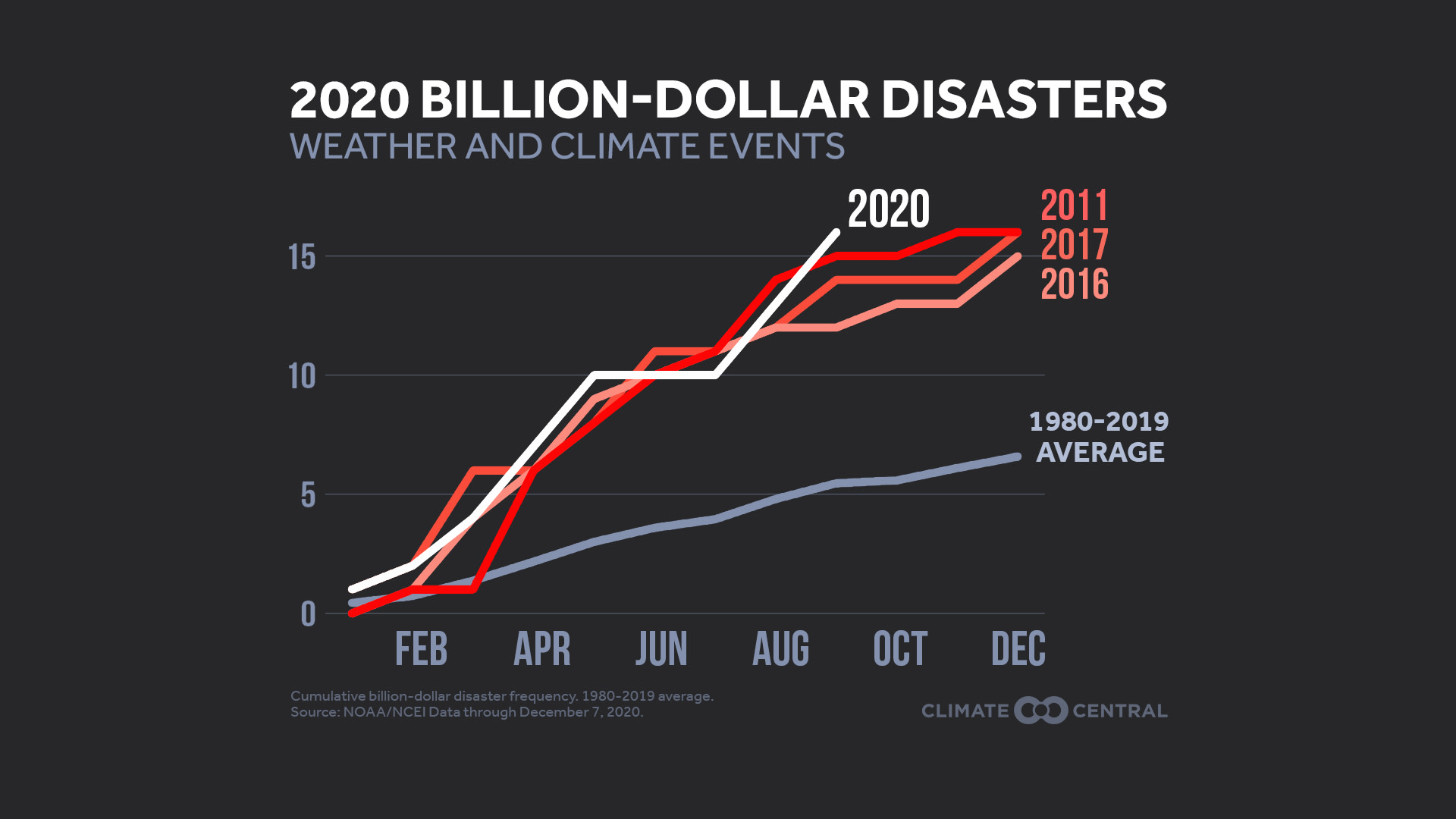

According to NOAA NCEI, 2020 is the sixth consecutive year in which the U.S. has experienced 10 or more billion-dollar weather- and climate-related disasters, compared to the 1980-2019 average of 6.6 events per year. It may take some time to assess the full impact of the 2020 disasters; so far the toll is 188 lives lost and $46.6 billion dollars and counting.

In the midst of the pandemic, tens of thousands of Americans were forced to flee their homes. The American Red Cross reported that it provided over 1.2 million overnight stays to evacuees (quadruple the number provided in an average year) and emergency financial assistance to 11,800 households, primarily in response to wildfires and hurricanes.

Weather-related disasters can result in significant life upheavals that are challenging to quantify such as job loss, relocation, and rupturing of social networks. These impacts can in turn give rise to mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse.

The impacts are often greatest among lower income communities, which are likely to be most vulnerable to disasters through financial insecurity (e.g. access to savings, difficulty qualifying for disaster loans and assistance), housing disparities (e.g. lower rates of home ownership, losses of affordable housing), and more limited access to healthcare insurance.

Find All Image Types Here (JPG & PNG)

What more fitting end could there be to a year like 2020 than to review the disasters we’ve experienced—weather- and climate-related disasters, that is. 2020 is the sixth consecutive year in which the U.S. has experienced 10 or more billion-dollar disasters, compared to the 1980-2019 average of 6.6 events per year (according to the latest quarterly report from NOAA NCEI). In addition to three landfalling hurricanes, this year’s disasters involved 11 severe local storm events—which included three tornadoes and two hailstorms. Drought and the Western wildfires are also in the list.

Assessing the full impact of these disasters will continue into 2021, so the final number and their cossts are set to rise. The cost for this year’s billion-dollar disasters currently stands at approximately $46.6 billion dollars and counting, with 188 lives lost. In the midst of the pandemic, tens of thousands of Americans across the country were forced to flee their homes. The American Red Cross reported that it provided over 1.2 million overnight stays to evacuees (quadruple the number provided in an average year) and emergency financial assistance to 11,800 households, primarily in response to wildfires and hurricanes. In Louisiana, over 70,000 applications for individual assistance were filed in August in the wake of Hurricane Laura—the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the state in 150 years. In Iowa, the August derecho impacted almost four million crop acres, dealing yet another blow to farmers.

Immediate emergency assistance is the first part of disaster response, but the recovery process can continue for years after the disaster—sometimes still ongoing when the next disaster hits. Weather-related disasters can result in significant life upheavals that are challenging to quantify such as job loss, relocation, and rupturing of social networks. These impacts can in turn give rise to mental illnesses such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse. And the impacts are often greatest among lower income communities, who are likely to be most vulnerable to disasters through financial insecurity (e.g. access to savings, difficulty qualifying for disaster loans and assistance), housing disparities (e.g. lower rates of home ownership, losses of affordable housing), and more limited access to healthcare insurance.

If 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that we do not want to find ourselves unprepared when a crisis strikes. Climate change is already exacerbating both the frequency and severity of many weather and climate-related disasters so it’s imperative that we double down on our efforts to adapt. This means developing resilience to disasters, but also mitigating climate change by lowering greenhouse gas emissions in order to halt warming and avoid the worst projected impacts.

POTENTIAL LOCAL STORY ANGLES

How expensive are the disasters affecting your local area?

Pew Trusts report that there are challenges to assessing state spending preparation for and recovery from disasters. You can search for current and historical National Flood and Insurance Program (NFIP) policy and claims statistics by state or county, including information about significant historical flooding events. And you can find more state-level statistics on insurance claims at the Insurance Information Institute.

Tools for reporting on extreme weather events and disasters near you:

A number of journalism schools and organizations provide advice for responsibly reporting on disasters, including focusing on safety, data, and cultural sensitivity. You can find preparedness materials for hurricanes, flooding, and other health emergencies at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In addition, you can uncover more information about extreme weather events with Climate Central’s Extreme Weather Toolkit and through SciLine’s multiple fact sheets. The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting also provides examples of stories on a range of topics and issues that intersect with crisis reporting, such as climate change, coastal populations, and indigenous communities.

After disasters, what hazard mitigation or adaptation measures are happening in your local area?

The U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit discusses climate impacts by region of the country. It also provides links to numerous government agencies, tools for assessing hazards, and case studies of adaptation and resilience efforts around the country. And the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri has created a reporters’ guide to climate adaptation.

LOCAL EXPERTS

The National Voluntary Organization Active in Disasters (VOAD) is an association of organizations that seeks to mitigate and alleviate the impacts of disasters in communities. You can find your state’s VOAD website, where you can discover state organizers as well as local member organizations. You can also find your local Emergency Management Agency through the FEMA website, as well as Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) in your area.

The SciLine service, 500 Women Scientists or the press offices of local universities may be able to connect you with local scientists who have expertise on climate-related disasters in your area. The American Association of State Climatologists is a professional scientific organization composed of all 50 state climatologists.

NATIONAL EXPERTS

Monica Sanders, J.D., LL.M, Associate Professor, Univ. Delaware, Faculty Georgetown Emergency Management Program. Research Interests Include: emergency management. msanders@udel.edu or (301) 642-9225.

Susan Clayton, Ph.D., Whitmore-Williams Professor and Chair of Psychology, The College of Wooster. Research Interests Include: climate change and psychological well-being. sclayton@wooster.edu.

METHODOLOGY

Data source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2020). https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/, DOI: 10.25921/stkw-7w73. The cost has been adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The methodology developed by NOAA NCEI, with input from economic experts and consultants to remove biases, can be found at https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/overview. Additional review of the methodology can be found in Smith and Katz, 2013. For even more context, see FAQ here.