The first of April is the end of the wet season across the West, the time of year when the region gets most of its precipitation. As such, it is a good time to take inventory of the snowpack in the mountains. The snow readings are important during this time of the year, as several locations depend on the meltwater from that snowpack for drinking water and irrigation through the drier and hotter summer months. It also serves as a long-term measurement, as in a warming world, the spring snowpack will melt more quickly as summer nears.

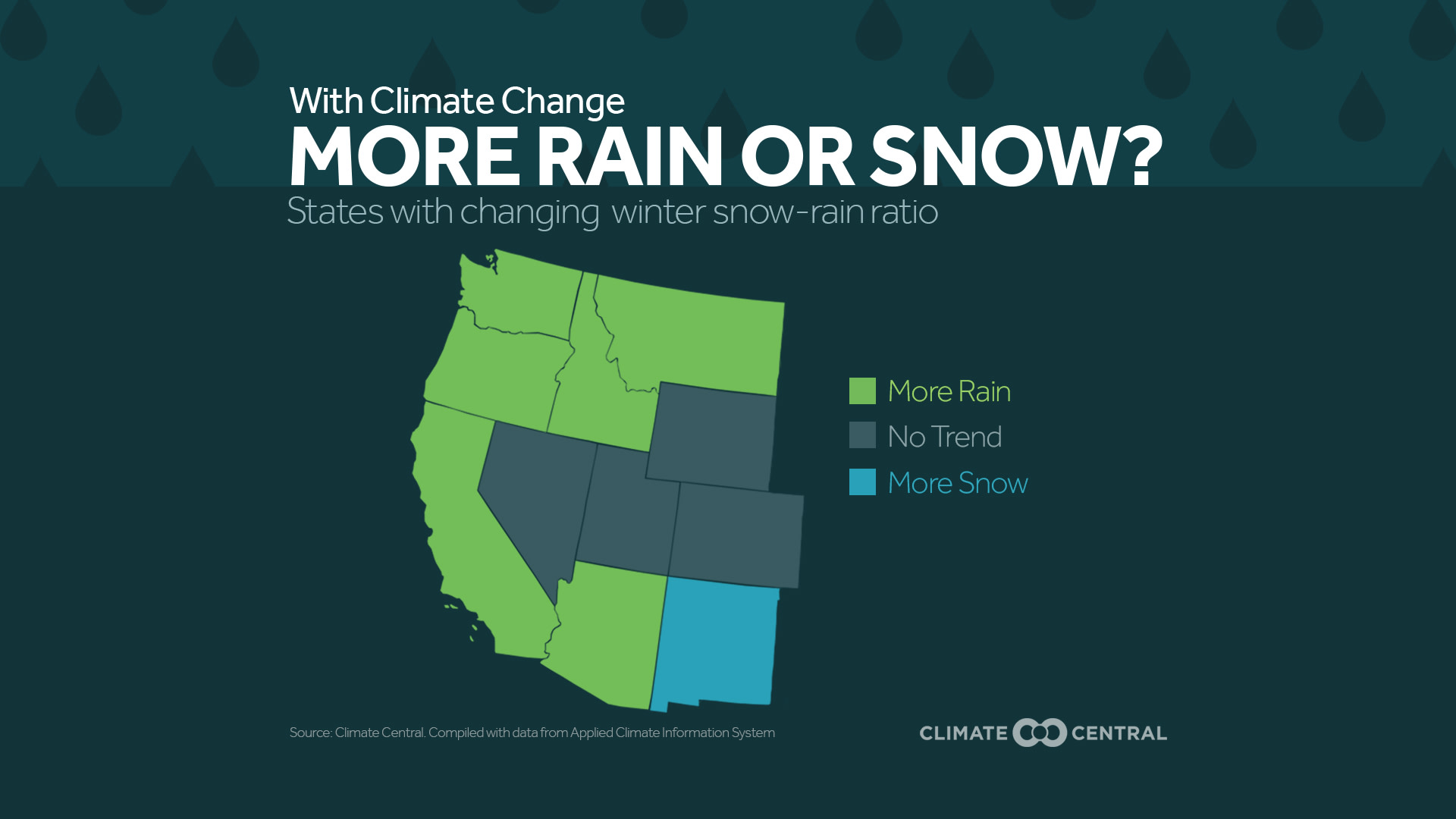

While the western snowpack levels have improved over last year’s dismally low levels overall, there are still places below average in Colorado, Montana, and New Mexico. Given that the long-term trend in early spring snowpack is down, Climate Central recently examined how the type of precipitation is changing during the winter months nationwide. In our new expanded report, “Meltdown”, we have analyzed the role of elevation in the percentage change of winter precipitation falling as rain. The analysis began with over 3,000 Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN) stations with available precipitation data. The stations used in the final analysis were selected based on whether or not they receive snow on a regular basis. A full methodology can be found in the report.

Some findings since 1949:

Nationwide, elevations up to 5,000 feet had 66% of their stations indicate a decrease in the percentage of precipitation falling as snow in the winter.

In California, 62% of the stations are reporting a decrease in the percentage of precipitation falling as snow in the winter.

In Arizona, 83% of its stations between 2,000 to 5,000 feet show a decrease in the percentage of precipitation falling as snow in the winter.

Elevations between 2,000 to 5,000 feet in Washington State had 63% of their stations report a decrease in the percentage of precipitation falling as snow in the winter. Below 2,000 feet, that number jumps to 81%.

Also troubling, the percentage of the West in drought has been on a long-term increase since the beginning of the 20th century. The frequency of droughts also strains water supplies and increases the risk for wildfires. While the drought has eased for much the West in the last 12 months, it has not been eliminated.

Most of Central California remains in Exceptional Drought, practically unchanged from last year. And even though increased precipitation from this year’s El Niño has helped in the Sierra, the snowpack is only slightly above normal. Meanwhile, Southern California has missed out on beneficial precipitation — Los Angeles and San Diego each had about two-thirds of their normal rain since December 1.

Only two Western states, Washington and Oregon, had above average precipitation during the winter. The remaining western states had normal, or even slightly below normal precipitation. This serves as a reminder that El Niño is not a cure-all for western drought.