The National Park Service (NPS) turned 103 years old this week. Since their inception on August 25th, 1916, America’s national parks have become treasured areas of wilderness and beauty among American and international tourists, exceeding 318 million visitors in 2018.

How has the temperature been changing in your favorite national park?

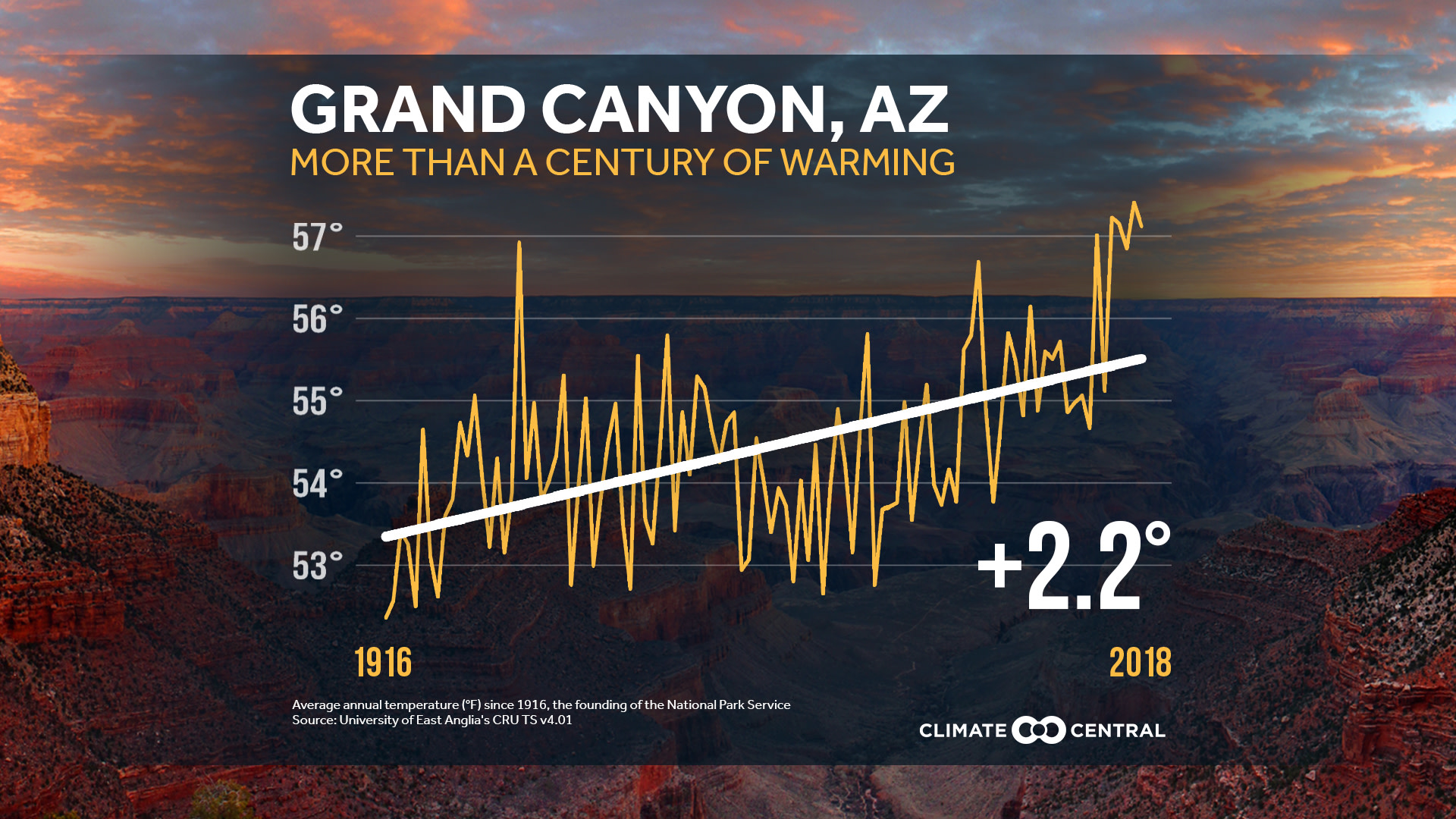

We updated our earlier analysis of historical temperatures in 62 national parks and found that all but one of the parks analyzed showed a warming trend since 1916. Of those parks, 39 have experienced two degrees F or more of warming in that period. Eight of the top ten warming parks are all outside the contiguous U.S.—in Alaska, Hawaii and the Virgin Islands.

The past century’s warming temperatures are strongly correlated with climbing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. And as carbon dioxide levels continue to rise, warming will continue. Looking to the future, the NPS is preparing for changes in visitation due to human-caused climate change. A 2015 Park Service study found that warming could result in a net extension of the primary visitation season when looking at all parks, which could lead to more visitors. However, some parks with historically warm temperatures (mostly found in southern latitudes) may see a decrease in visitation during the hottest months of the year.

Here are other Climate Central media resources for National Parks:

Find out what future warming could look like in each park

Imagine how future shifting of park climates could feel to visitors

Explore a special report which includes sections on management costs and conservation

While the U.S. as a whole is already seeing strong warming effects, a 2018 study published in Environmental Research Letters found that park areas have warmed at twice the national rate between 1895 and 2010. Reflective snow and ice in many parks is disappearing, meaning more solar energy is absorbed by the ground, raising temperatures further. And for national parks in the southwestern U.S., warming exacerbates dry conditions and leads to prolonged periods of drought, drier soils and reduced spring snowpack.

Across all parks, climatic warming is already driving a range of impacts, such as heavy rain, seasonal shifts, coastal and soil erosion, habitat degradation, poor air quality and invasive species. These impacts threaten some of the most iconic and prized features of our favorite parks, many of which—like the glaciers of Glacier National Park, the historical Fort Jefferson at Dry Tortugas National Park and the ancient Pueblo cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde National Park—can never be recovered.

METHODOLOGY: Climate Central analyzed average annual temperature trends at 62 National Parks since 1916 using the University of East Anglia's CRU TS v4.01 dataset. Temperatures were averaged across all areas within 30km of park boundaries (Monahan and Fisichelli 2014). Trends are based on linear regression analysis.