KEY CONCEPTS

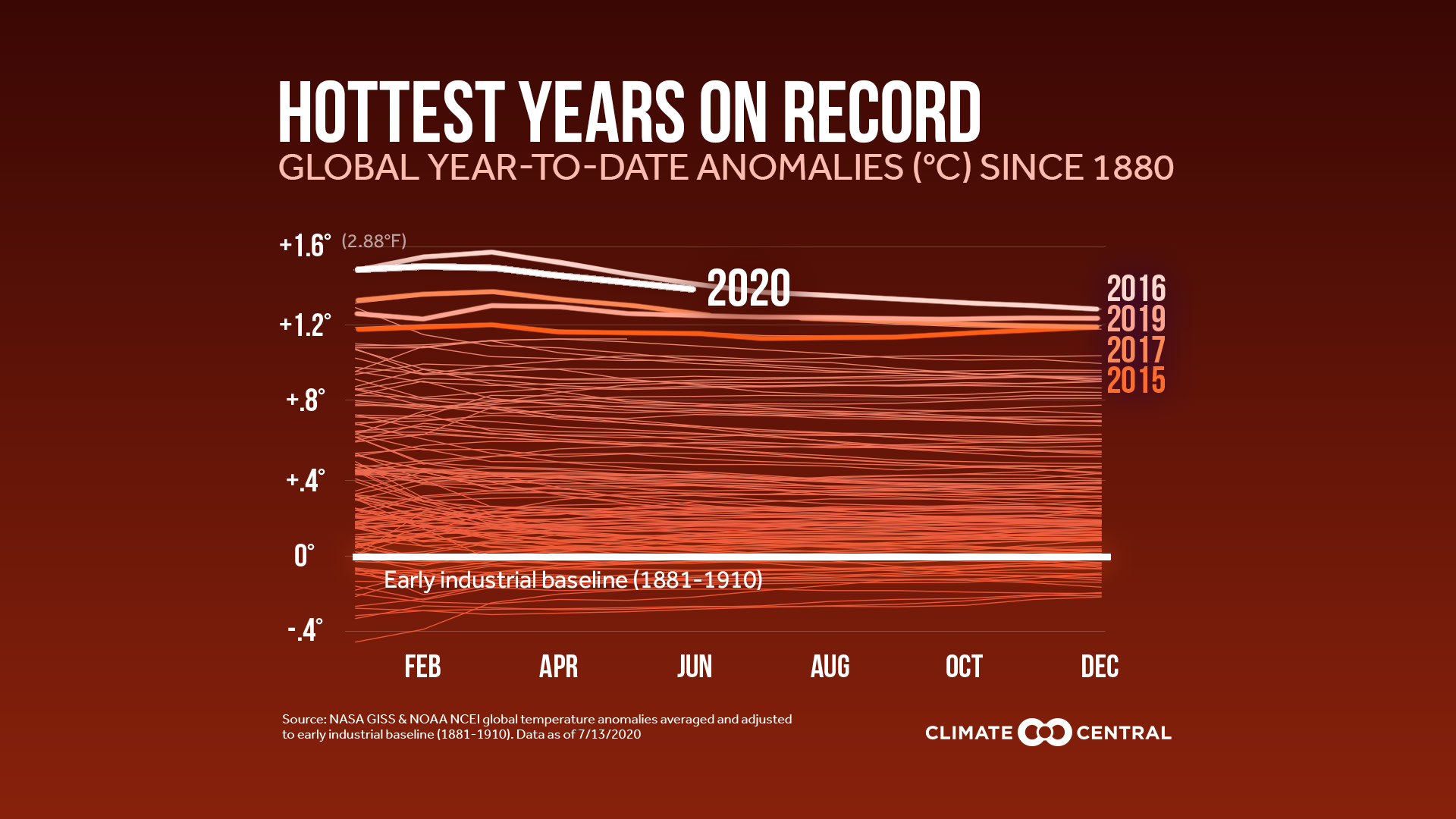

Using combinedNOAA and NASA data, we find that 2020 has been the planet’s 2nd-hottest year on record through June.

Year-to-date temperatures are 1.36℃ (2.45℉) above a 1881-1910 baseline—approaching levels from the record-setting year of 2016. This year is 90% likely to finish among the top three.

Warming will continue as long as we emit greenhouse gases. While emissions temporarily declined this spring during global shutdowns, they are quickly rising back to normal in much of the world.

With the release of June global temperatures from NOAA and NASA, the results are in for the first half of 2020. Even in this tumultuous time, the Earth is still warming—as continued greenhouse gas emissions lead to near-record temperatures once again. Using combined NOAA and NASA data, we find that 2020 has been the planet’s 2nd-hottest year on record so far.

The statistics are striking:

This year is ‘virtually certain’ to finish among the top five, which would make the seven latest years the seven hottest in 140 years of records.

2020 also has a 36% chance to eclipse 2016 as the hottest on record, even without an El Niño—the pattern that propelled 2016 to its record heat.

Year-to-date temperatures are 1.36℃ (2.45℉) above a rebaseline from 1881-1910, which indicates warming since the early industrial era.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, the next five years may stay at least 1℃ above pre-industrial levels, and even approach the Paris Agreement’s aspiration of a 1.5℃ limit.

June was the 426th consecutive month with temperatures above the 20th century average.

These numbers are even more extreme near the poles. On June 20, the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk reached 100.4℉—an earth-shattering Arctic record that was later confirmed by Russia’s meteorological service. Parts of Siberia were up to 18℉ hotter than normal in June, leading to a record wildfire season with the highest estimated CO2 emissions in 18 years of monitoring.

What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. When these wildfires burn and polar permafrost thaws, even more greenhouse gases are released to heat our planet. A similar vicious cycle occurs with melting sea ice, which is near a record-low as well. The Arctic is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the world.

Other regions have felt the heat too. Antarctica broke temperature records in February, and sustained heat this year has covered the globe from Northern Europe to South America. In the U.S., South Florida has observed 134 record highs (and counting) this year, and only one record low—a stunning reminder of this imbalance in most areas. Through June, the U.S. has had its 8th hottest year out of 126 on record.

Warming will continue as long as we emit greenhouse gases. While emissions declined this spring during global shutdowns, they are quickly returning to normal in much of the world. From renewable energy to smarter agriculture to education, it will take major changes to bend the rising curves of CO2 and global temperatures.

NATIONAL EXPERTS

Ahira Sánchez-Lugo — Physical Scientist, NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), Center for Weather and Climate (CWC), Ahira.Sanchez-Lugo@noaa.gov

*Available for interviews in Spanish and English

Jennifer Brady — Senior Data Analyst, Climate Central, jbrady@climatecentral.org

METHODOLOGY

Monthly global temperature analyses are independently calculated by NASA and NOAA/NCEI. Climate Central combines the NOAA and NASA information to re-baseline global temperatures using an earlier pre-industrial baseline of 1881-1910 in response to the Paris Climate Change Agreement. NASA’s calculations are extended to account for temperature changes at the poles, where there are fewer stations. NOAA does not use any extrapolation to account for low station density at the poles.