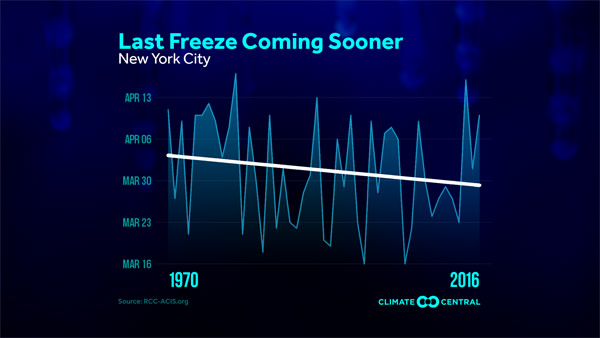

The growing season is underway in parts of the U.S., primarily in the Southeast. As the world warms, the average date of that last spring freeze is occurring earlier in the year, extending that season. While the longer growing season does have some benefits, it also raises concerns about both agriculture and health.

Consistently warmer weather helps pests survive longer while also stressing crops and potentially decreasing yields. Each crop thrives in a favored temperature range, so net warming can lead to a geographical shift in areas that have been historically productive for a particular crop. Correspondingly, higher overnight temperatures tend to reduce the productivity and quality of grains and fruits, which can drive up the cost of produce at the supermarket.

A longer growing season also means a longer allergy season, as pollen counts rise with the longer season and higher levels of carbon dioxide. And disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes can survive warmer winters and thrive in most locations during the summer.

As the concentration of greenhouse gases rises and the planet warms further, there will continue to be a decrease in the average number nights below freezing. Without any change in the rate of greenhouse gas emissions, most of the U.S. is projected to have an extra month or more of nighttime lows above freezing by the end of the century compared to the end of the 20th century.

Locations without a consistent freezing season (defined as fewer than 30 annual nights of sub-freezing temperatures) were excluded from the analysis. Projection in the loss of days with minimum temperatures below 32°F is based on the A2 emissions scenario (the emissions path that we are currently on) from the 2014 U.S. National Climate Assessment, comparing the period 1971-2000 to the projections for 2070-2099.